In 2012, Ohio authorities detected a new apparent disease attacking American beech (Fagus grandifolia) in Northeast Ohio. Initially they observed decline and mortality of beech saplings. Over the four years between 2012 and 2016, the apparent disease, termed beech leaf disease (BLD), spread from an estimated 84 ha to 2,525 ha within Lake County, Ohio (Ewing et al. 2018) (see also pages on beech bark disease [BBD] and beech leaf-mining weevil [BLMW]).

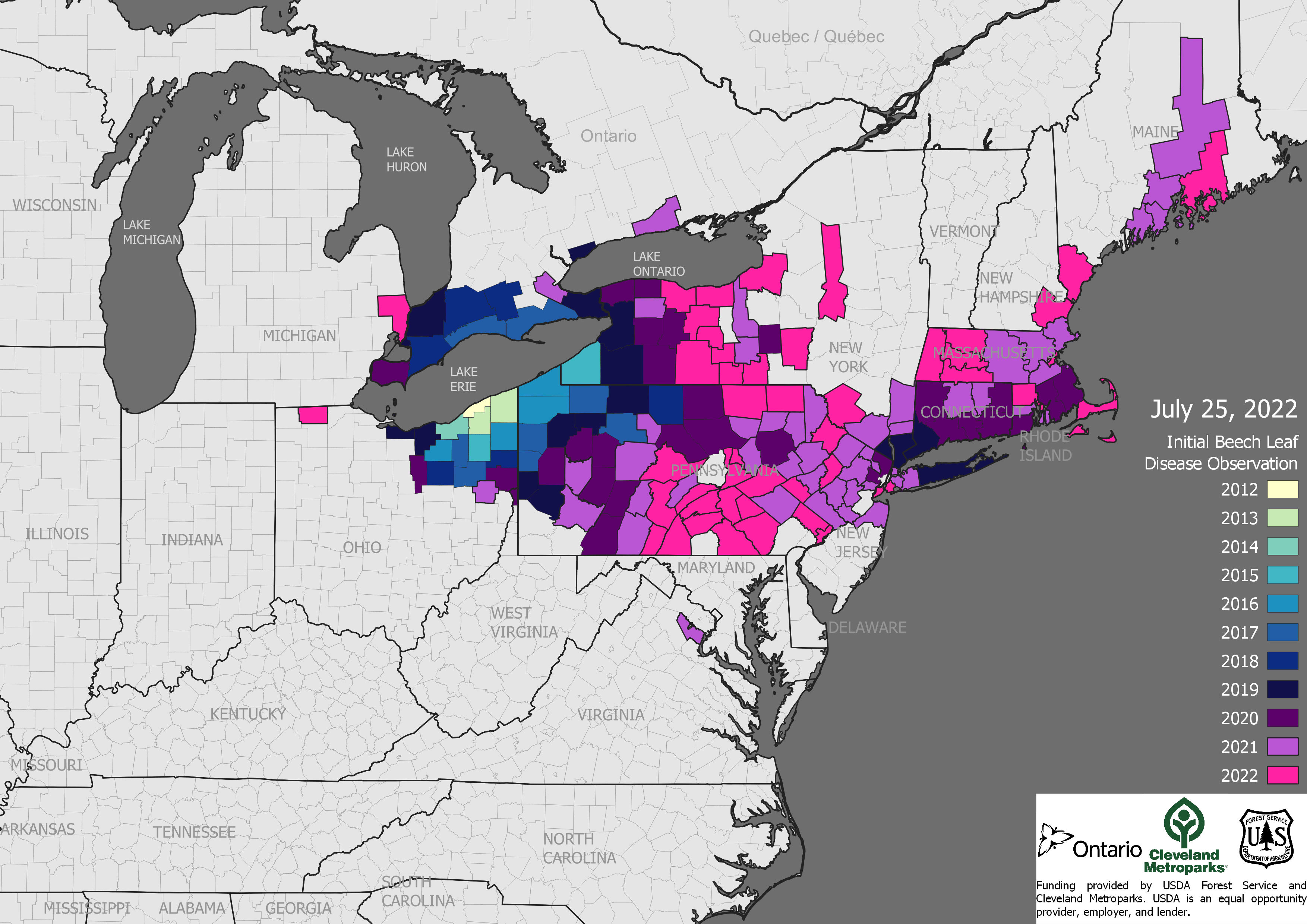

In December 2020, Daniel Volk with Cleveland Metroparks sent out this update via email to a list of stakeholders, “There was a tremendous effort to survey for BLD in 2020 and the (below) map is a product of these efforts. In total, we added four new states (Massachusetts, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and West Virginia) and 31 new counties, totaling 71 counties with BLD across the US and Canada.” In 2021, outbreaks were detected in Maine and Virginia (Gianino, 2021 and Smith, 2021). Maps and other information are available at https://www.clevelandmetroparks.com/parks/education/publications. An updated USFS Pest Alert is now available here: USFS Beech Leaf Disease Pest Alert

The rate of decline within beech stands varies, suggesting that trees differ in susceptibility. This is a promising for breeding resistance (Ewing et al.).

Most scientists now agree that the cause is a non-native nematode. Japanese researchers described a previously un-named nematode as Litlylenchus crenatae in May 2018 after studying it on Japanese beech F.crenata (Kanzaki et al.). The U.S. population (found by David McCann of the Ohio Department of Agriculture) was later described as a subspecies Litylenchus crenatae ssb mccannii by Lynn Carta. Thousands of live Litylenchus nematodes (at least 10,000) can swim out from a single infested leaf.

Symptoms

Early symptoms are dark striping on the leaves – best seen by looking upward into the backlit canopy. The striping is formed by a darkening and thickening of leaf tissue between leaf veins. Later, lighter, chlorotic striping may also occur. Eventually the affected foliage withers, dries, and yellows. Bud and leaf production is also affected. Drastic leaf loss does occur for heavily symptomatic leaves during the growing season, as early as June, but asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic leaves show no or minimal leaf loss respectively. Both fully mature and very young “emerging” leaves show symptoms.

Disease Progression

In Northeast Ohio, intensive monitoring of a subset of 13 plots in Cleveland Metroparks sites revealed a 7% mortality rate in 2018, primarily in saplings (Volk, pers comm). More than half of the plots now have dead trees that had previously been only symptomatic. While most of the dead trees are less than 4.9 cm dbh, some larger trees have died and others bear only a few leaves in summer. Sapling and pole-sized trees die within about three years after symptoms are observed. In areas where the disease is established, the proportion of American beech affected nears 100% (Pogachnik 2016).

Disease incidence does not appear to be influenced by slope, aspect, soil conditions, or weather. Also, while a wide variety of insects and pathogens is associated with symptomatic trees, these appear to be independent of beech leaf disease.

Leaves with light, medium, or heavy symptoms of infection – as well as asymptomatic leaves – can occur on the same branch of an individual tree.

The disease may spread through beech clone clusters along the interlocking roots, rain splash, and biotic vectors such as through contact with songbirds (external or via consumption of plant materials).

Long range spread of the disease is probably assisted by anthropogenic transport, especially of nursery stock. Both European (F. sylvatica) and Asian (F. orientalis) beech have shown symptoms (Ewing et al. 2018). In the past, an Ontario retailer received – and rejected – a shipment of diseased beech from an Ohio nursery.

Online references

Beech Leaf Disease Publications, Cleveland Metro Parks https://www.clevelandmetroparks.com/parks/education/educational-resources/publications

Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Forestry, Beech leaf disease page https://ohiodnr.gov/wps/portal/gov/odnr/discover-and-learn/safety-conservation/about-ODNR/forestry/forest-health/insects-diseases/Beech-leaf-disease

Beech Leaf Disease, New York Department of Environmental Conservation, https://www.dec.ny.gov/lands/120589.html

Sources

Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. 2019. CAES Announces First Report of Beech Leaf Disease in Greenwich, New Canaan, and Stamford Connecticut. Press Release. October 17, 2019.

Ewing, C.J., C.E. Hausman, J. Pogacnik, J. Slot, P. Bonello. 2018. Beech leaf disease: An emerging forest epidemic. Short Communication. Forest Pathology 2018;e12488

Gianino, D. 2021. (Virginia) Presentation at the 95th annual meeting of the National Plant Board, July 28, 2021.

Kanzaki, N., Y. Ichihara, T. Aikawa, T. Ekino, and H. Masuya. 2019. Litylenchus crenatae n. sp. (Tylenchomorpha: Anguinidae), a leaf gall nematode parasitising Fagus crenata Blume. Nematology. Volume 21: Issue 1

John Pogacnik, Biologist, Lake Metroparks & Tom Macy, Forest Health Program Administrator, Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry. Forest Health Pest Alert Beech Leaf Disease July 2016

Potter, K.M., Escanferla, M.E., Jetton, R.M., Man, G., Crane, B.S., Prioritizing the conservation needs of US tree spp: Evaluating vulnerability to forest insect and disease threats, Global Ecology and Conservation (2019), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/

Smith, G. 2021. (Maine) Presentation at the 95th annual meeting of the National Plant Board, July 28, 2021.

Photo Credit: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation