Guest blog by Laurel Downs, The Nature Conservancy

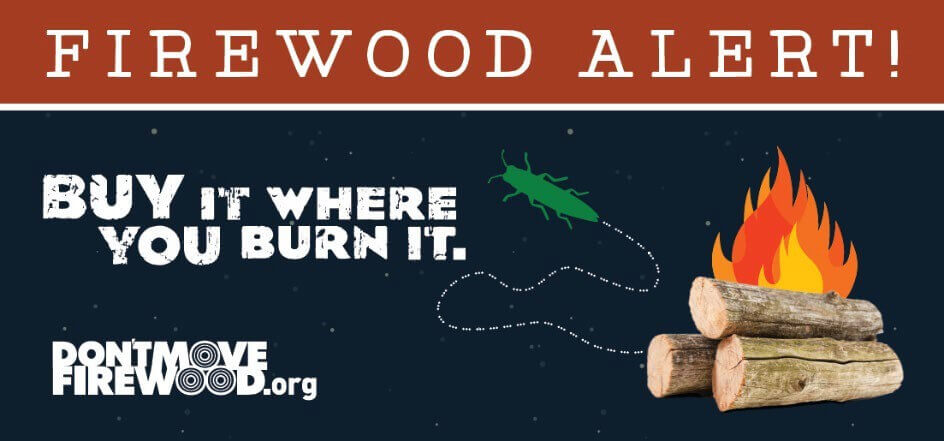

The overall goal of the Don’t Move Firewood campaign boils down to protecting trees in North America from destructive pests and diseases. We want to heighten awareness around the fact that infested or contaminated firewood is one of the most common ways by which invasive forest pests spread to new areas. We provide direct and simple information on 1) how firewood can spread pests, 2) the pests themselves, and 3) what practices we recommend to avoid spreading pests on firewood. This is a classic educational effort to change human behavior; people can help protect trees by making responsible firewood choices.

Simple, right?

If only. Turns out people are much more complicated than that, and stacks on stacks of research suggests that information alone is not enough. A science communication strategy that assumes people will alter their behavior with new information – the knowledge-deficit model – often falls short because factors such as values, attitudes, social norms (essentially the desire to fit in), and socioeconomic circumstances are key drivers of human behavior. To be effective, our campaign’s messaging needs to not only inform, but appeal to the wildly variable population that our campaign aims to reach- basically anyone and everyone who ever uses firewood.

Thus emerges the profoundly important old adage “it’s not what you say, but how you say it.” Except, now we know that it also matters when you say it. And how often. And in what context. And with what graphics. And on what platform… because merely getting the word out morphs into somewhat of a monumental task when you consider the competitive digital landscape the whole world now deals with. Ads, current events, politics, social media, and other modern-day distractions bombard the senses of just about everyone with an internet connection. The complex algorithms that generate much of what we see day-to-day online can be an obstacle as well, since our conservation-based communications are likely to disproportionately reach people who are already conservation-minded. Many of the folks we reach may already know about the risks involved with moving firewood. In other words, we might be preaching to the choir… and that wastes time and money. We need to reach everyone in the big tent original audience- i.e., all firewood users.

Whew. So many obstacles. How do we cope? Why do we try?

Well, because anyone who is passionate about conservation knows we’ve got to keep on truckin’. It’s true that passing along the straight-forward notion of using local firewood presents a challenge in and of itself. It’s also true that even when our message manages to escape the void, bounce off the choir, and finally inform a new firewood user, it may not change their behavior. But it’s a crucial first step. And in our efforts to navigate the complexity of the human psyche, we put painstaking thought into Every. Single. Word. (Sometimes every syllable! Check out our Facebook page for our new “Hump Day Haiku” series every Wednesday. It’s fire.)

Thankfully, we’re not making our communication choices in the dark. Many years of research help inform our wording, the audiences we try to reach, and even what sorts of graphics we use. Most recently, the Don’t Move Firewood campaign collaborated with researchers at Clemson University to help better understand their big public polling datasets on the most effective phrasing and messengers for a positive response among the public; that research should be published soon so that everyone can benefit from the in-depth look it provides. Additionally, this past summer the Don’t Move Firewood campaign hired summer analysts who spent countless hours researching, synthesizing, and translating stiff regulatory information into succinct summaries so folks can quickly learn the firewood rules and recommendations in their area or destination (see our Firewood Map). We also regularly reach out to diverse stakeholders and coordinate with governmental, non-governmental, academic, and industry partners alike to amplify important firewood messaging as well as keep our information up-to-date.

Ultimately, while the inner workings of our outreach campaign are complex, we try to keep our message as simple as possible. Prevention is our best defense against invasive species, and everyone has the power to take preventative measures to protect our forests. For starters, please… Don’t Move Firewood.